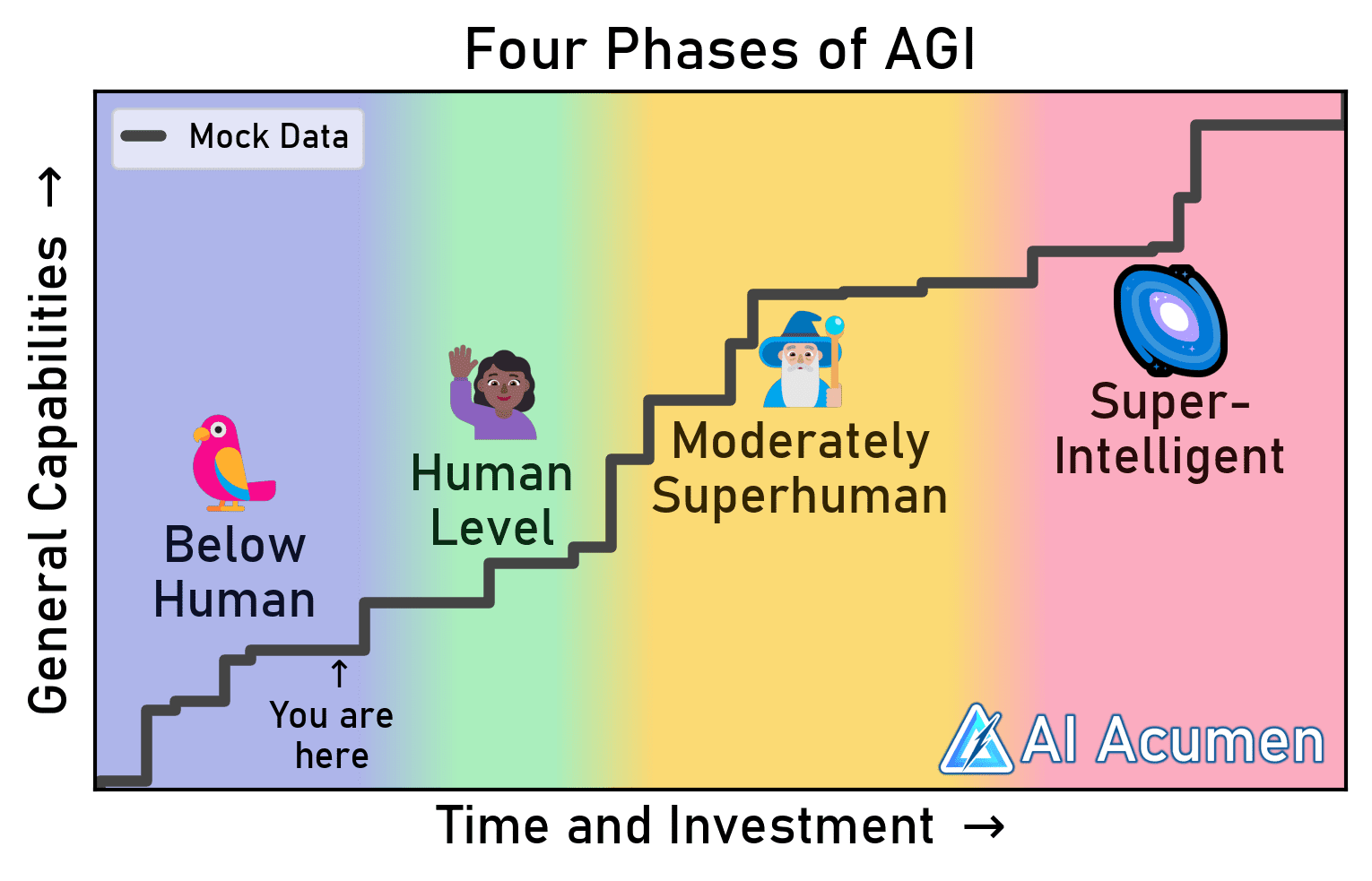

we are still split into two groups on what AGI means, despite the latest model releases:

— Haider. (@slow_developer) June 5, 2025

- LLMs are not the path to AGI

- scaling llms will lead to AGI

so, which side makes more sense to you here?

That's precisely what I've been saying.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) June 6, 2025

Thank you @sundarpichai https://t.co/iEgs6jDxpB

Here is a balanced argument presenting both sides of the ongoing debate around whether scaling Large Language Models (LLMs) will lead to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI):

Argument 1: LLMs Are Not the Path to AGI

-

Statistical Mimicry ≠ Understanding

LLMs are fundamentally pattern-recognition engines trained to predict the next token. They do not “understand” meaning, intentions, or goals. They simulate reasoning without possessing it, and lack grounding in real-world context, embodiment, or sensory experience—critical aspects of general intelligence. -

Lack of Agency and Autonomy

LLMs do not initiate goals, pursue objectives, or act independently in the world. AGI requires agency: the ability to plan, adapt, and act toward long-term goals across environments, which LLMs are not designed to do. -

Catastrophic Forgetting and No Long-Term Memory

LLMs do not learn continually or adapt dynamically post-training. Their knowledge is static, baked into weights. AGI requires lifelong learning, updating beliefs in real time, and managing long-term memory—which current LLM architectures do not support robustly. -

Scaling Laws Show Diminishing Returns

While LLM performance improves with scale, there's growing evidence of diminishing returns. Bigger models are more expensive, harder to align, and less interpretable. Simply scaling does not necessarily yield fundamentally new cognitive abilities. -

Missing Cognitive Structures

Human cognition involves hierarchical planning, self-reflection, causal reasoning, and abstraction—abilities that are not emergent from LLM scaling alone. Without structured models of the world, LLMs cannot reason causally or build mental models akin to humans.

Argument 2: Scaling LLMs Will Lead to AGI

-

Emergent Capabilities with Scale

Empirical evidence from models like GPT-4 and Gemini suggests that new abilities (e.g. multi-step reasoning, code synthesis, analogical thinking) emerge as models grow. These emergent behaviors hint at generalization capacity beyond narrow tasks. -

Language as a Core Substrate of Intelligence

Human intelligence is deeply tied to language. LLMs, by mastering language at scale, begin to internalize vast swaths of human knowledge, logic, and even cultural norms—forming the foundation of general reasoning. -

Unified Architecture Advantage

LLMs are general-purpose, trainable on diverse tasks without specialized wiring. This flexibility suggests that a sufficiently scaled LLM, especially when integrated with memory, tools, and embodiment, can approximate AGI behavior. -

Tool Use and World Interaction Bridges the Gap

With external tools (e.g. search engines, agents, calculators, APIs) and memory systems, LLMs can compensate for their limitations. This hybrid “LLM + tools” model resembles the way humans use external aids (notebooks, computers) to enhance intelligence. -

Scaling Accelerates Research Feedback Loops

As LLMs improve, they assist in code generation, scientific discovery, and AI research itself. This recursive self-improvement may catalyze rapid progress toward AGI, where LLMs design better models and architectures.

Conclusion

The disagreement hinges on whether general intelligence is emergent through scale and data, or whether it requires fundamentally new paradigms (like symbolic reasoning, embodiment, or causal models). In practice, future AGI may not be a pure LLM, but a scaled LLM as the core substrate, integrated with complementary modules—blending both arguments.

Will Scaling Large Language Models (LLMs) Lead To Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) https://t.co/EEEHE7PswC

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) June 5, 2025