Sergey Brin's Google Glass Adventures In Steve Jobsism

Mars, Google Glass, and the Zuck Helmet

A Short History of Billionaires Picking Fights with the Human Body

Every tech era has its signature delusion: the moment when a very smart person with a very large bank account decides that biology is merely a suggestion.

Sergey Brin had Google Glass.

Mark Zuckerberg had the VR helmet.

Elon Musk has Mars.

Different gadgets, same mistake.

When Visionaries Forget Humans Have Necks, Eyes, and Social Norms

Google Glass failed not because the technology didn’t work, but because humans did. People didn’t like being stared at by walking surveillance cameras. Turns out, society has unspoken rules like “don’t film me while I’m eating a burrito.” Glass wearers learned this the hard way—usually through social exile or light public ridicule.

Then came Zuckerberg’s helmet: a plastic crown promising a virtual universe, delivered with the subtlety of a scuba mask at a dinner party. Wearing it felt less like entering the metaverse and more like volunteering for a mild hostage situation. Neck strain, eye fatigue, isolation—basic human anatomy raised its hand and said, “Excuse me, this is a terrible idea.”

Both products shared a fatal flaw:

They assumed humans would adapt to machines, rather than machines adapting to humans.

Enter Mars.

Mars: The Ultimate Disrespect to Human Biology

If Google Glass annoyed society and VR helmets annoyed spines, Mars outright declares war on the human body.

Let’s review the Mars job description:

Gravity: ~38% of Earth’s

(Your bones: “We’re out.”)Atmosphere: Basically decorative

Radiation: Free, unlimited, and lethal

Commute: 6–9 months in a flying closet

Return policy: Unclear, possibly fictional

The human body evolved for Earth. We are not modular furniture. Our organs, muscles, vestibular systems, immune responses, and mental health are all calibrated to one very specific blue rock.

Mars asks us to live permanently in low gravity, inside sealed cans, eating processed food, with no trees, no oceans, and no room to stretch. That’s not pioneering. That’s extreme indoor living.

Claustrophobia for months. Isolation for years. Solar radiation gently rewriting your DNA like an overenthusiastic editor. Even Earth’s deepest oceans—dark, pressurized, terrifying—are more hospitable to human life than Mars.

At least underwater, gravity still works.

Mars isn’t a colony plan. It’s a stress test for how much discomfort humans will tolerate in the name of billionaire aesthetics.

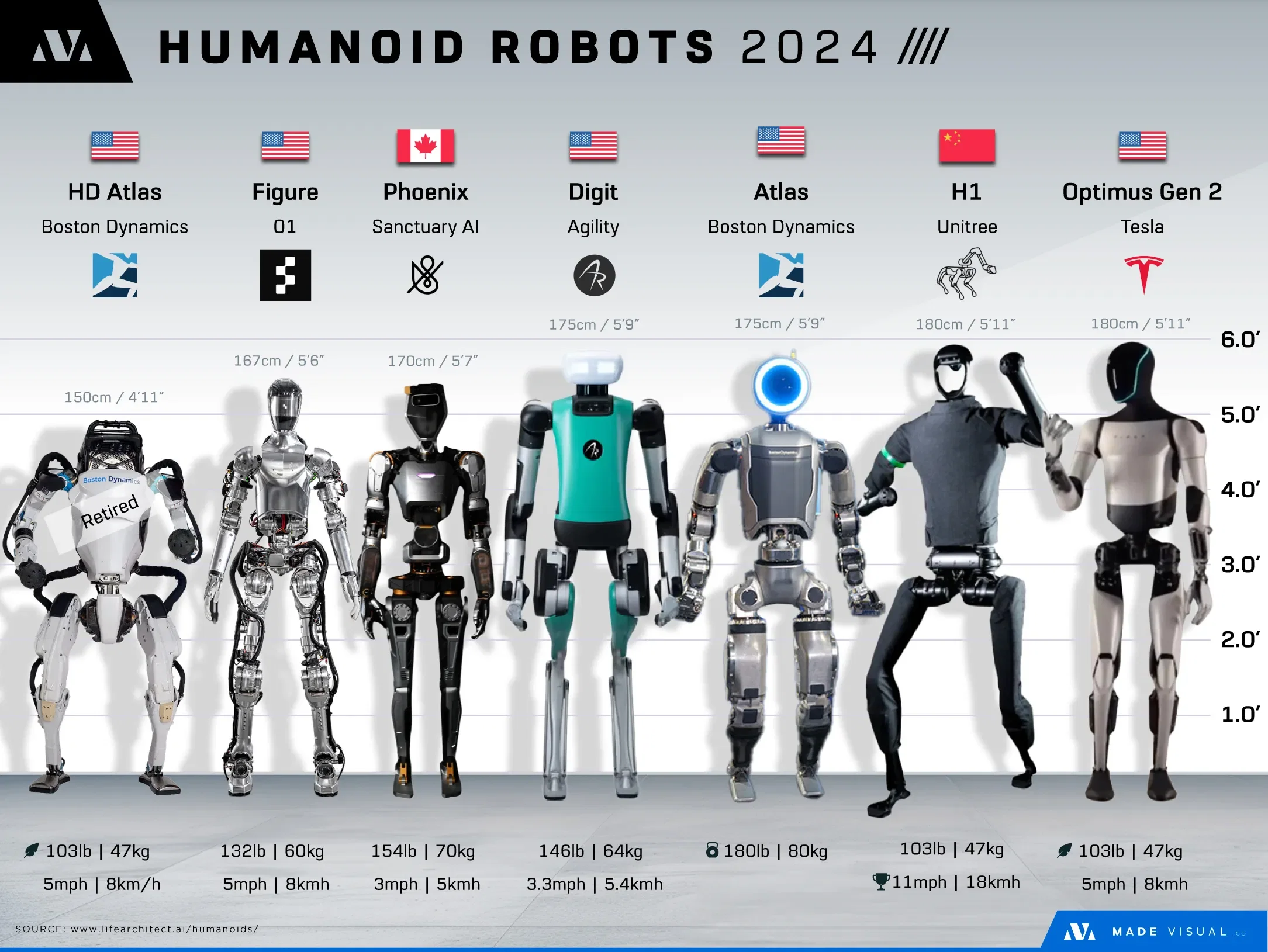

Robots: Yes. Humans: Absolutely Not.

Mars makes sense—for robots.

Robots don’t need gravity.

Robots don’t get lonely.

Robots don’t care if the sunset looks like a dusty Instagram filter.

Send machines. Build factories. Mine rocks. Study geology. Do science. That’s sensible.

But selling Mars as humanity’s backup plan is like suggesting we all move into server racks because the rent is cheaper.

It’s not courage. It’s a misunderstanding of what keeps humans sane.

The Real Space Economy Is Boring—and That’s Why It Works

Now here’s the twist ending the hype merchants hate:

Space is enormously valuable—just not in the sci-fi cosplay way.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is where the real revolution lives.

Global broadband

Earth observation and climate monitoring

Precision agriculture

Disaster prediction

Navigation, logistics, and timing systems

Manufacturing in microgravity

Space-based solar power (eventually)

LEO doesn’t require humans to abandon gravity, sunlight, or psychology. It enhances life on Earth, instead of trying to escape it.

This is the difference between:

“Let’s fix the planet using space”

and“Let’s abandon the planet because it’s inconvenient.”

One is engineering. The other is escapism with rockets.

The Pattern Is Clear

Google Glass failed because it ignored social biology.

VR helmets stumbled because they ignored physical biology.

Mars colonization fantasies persist because they ignore all biology at once.

The future doesn’t belong to people who shout “humans will adapt.”

It belongs to those who whisper, “humans matter.”

Build tools that fit faces.

Build systems that respect bodies.

Use space to improve Earth, not audition for exile.

Mars will still be there—cold, red, and unimpressed.

Just like the humans who took off the helmet, removed the Glass, and asked a very reasonable question:

“Why are we doing this again?”

Musk’s Management https://t.co/tD7n6ZojzF

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Yes, it is all about ethics. But techies get to stop acting like they are the first people in history to be bringing up these questions. Theologians. Talk to the theologians.

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Vitalik Buterin: Galaxy Brain Resistance https://t.co/nItd7uRMXi

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Mars, Google Glass, and the Zuck Helmet https://t.co/6cp6eFighW 🧵👇👆@elonmusk @Ashok_Elluswamy @MilanKovac @MahaVirudhagiri @Rajasekar_J @RiccardoBiasini @SteveDavisCEO

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

1/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Every tech era has its signature delusion: a billionaire deciding human biology is optional.

Sergey Brin had Google Glass.

Mark Zuckerberg had the VR helmet.

Elon Musk has Mars.

Same mistake. Bigger rockets. 🧵👇👆

3/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Then came Zuckerberg’s VR helmet.

A device that promised a digital universe but delivered neck pain, eye strain, and the vibe of a polite hostage situation.

Turns out humans like faces. And peripheral vision. 🧵👇👆

Mars, Google Glass, and the Zuck Helmet https://t.co/6cp6eFighW 🧵👇👆@Shivon_Zilis @Tesla_Engineering @Tesla_AI @TeslaMotors

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

6/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

Mars isn’t pioneering.

It’s extreme indoor living, with a 9-month commute and no return policy.

Even Earth’s deep oceans are more hospitable to humans. Gravity still works there. 🧵👇👆@Starlink @StarlinkStatus @Neuralink @NeuralinkAI @boringcompany

8/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

The real space revolution is boring—and that’s why it works:

Low Earth Orbit.

Satellites, broadband, climate monitoring, navigation, manufacturing.

Space improving life on Earth, not auditioning for exile. 🧵👇👆 @LoopLV @xAI @xAIresearch @GrokAI @X @XEng @XPlatform

10/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

The future doesn’t belong to “humans will adapt.”

It belongs to “humans matter.”

Build tech for bodies.

Use space to fix Earth.

And maybe… take the helmet off. 🚀🧠 🧵👇👆@TeslaOwnersPDX @Tesla_Hub @AI_at_xAI @xAIupdates

Tech Billionaires Can't Conquer Biology https://t.co/COSblT5Lc6 🧵👆 @elonmusk @Ashok_Elluswamy @MilanKovac @MahaVirudhagiri @Rajasekar_J @RiccardoBiasini @SteveDavisCEO

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) January 18, 2026

The path to the stars is the Moon and Mars https://t.co/OEpNYLWcpC

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) January 17, 2026

Building the future https://t.co/z2eEgYEza3

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) January 17, 2026